For electric utilities, even more than in most other industries, long-term planning is crucial. Two characteristics of the industry make this the case: it takes months to years to get a new generation, demand-side, or transmission project or program running, and historically it has been difficult and rare to store electricity, meaning supply and demand must always match at all times to avoid blackouts.

So the long-term planning process of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), a federally-owned utility that serves 10 million people across seven states in the Southeast, is a big deal. TVA is required to do this planning process, called an Integrated Resource Plan or IRP, at least every five years. Since the last one was finalized in 2019, TVA is due to finish its next plan by the end of next year. Last month, TVA started that ball rolling by opening a comment period for scoping comments through July 3. That “public input” period is essentially perfunctory, as you’ll see as I compare it to public processes done for IRPs elsewhere.

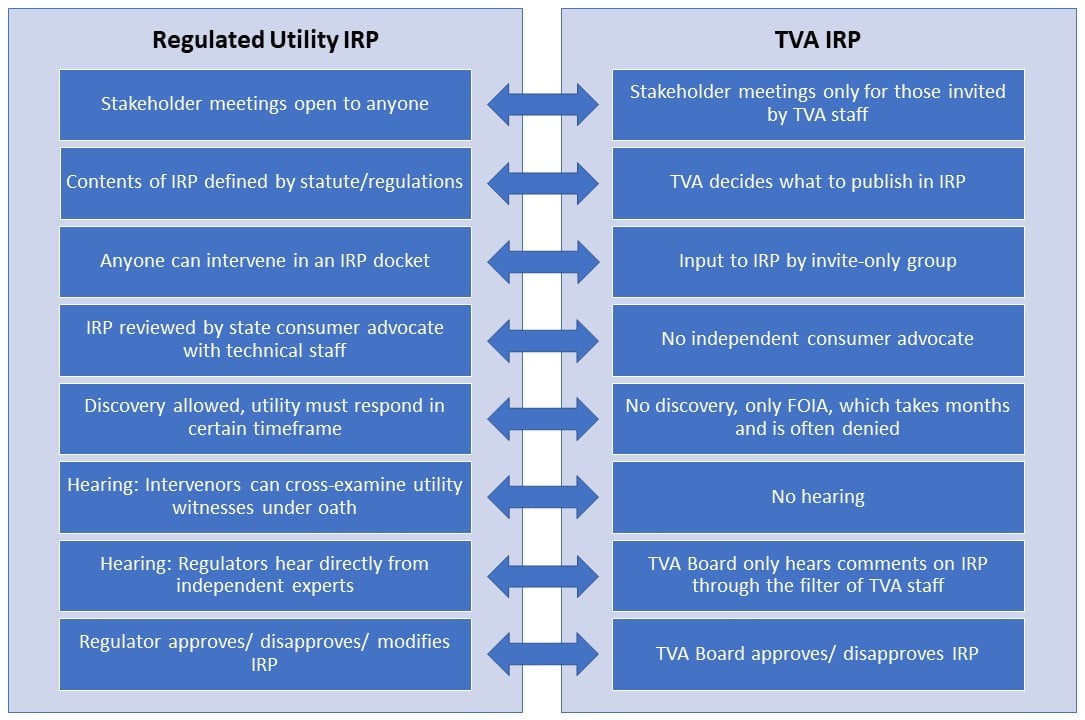

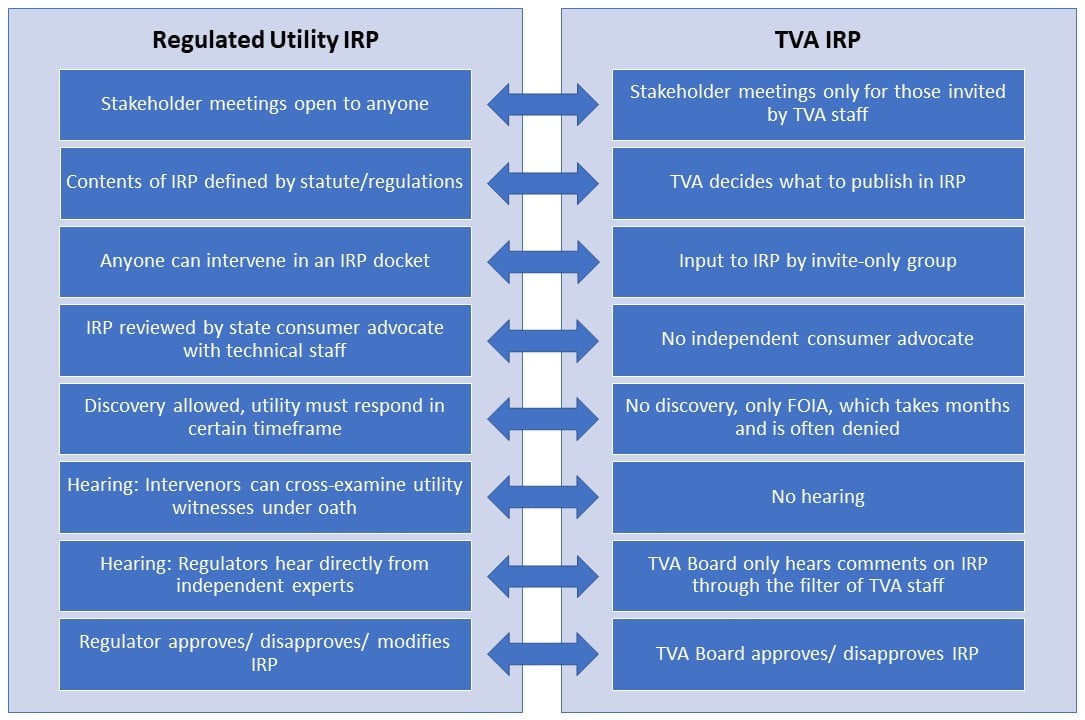

Before we embark on another TVA IRP process, it’s helpful to review how these processes have gone in the past, and how likely TVA is to consider your submitted comments in the long-term resource decisions it ultimately makes. Compared to IRP processes for utilities regulated by state Public Service Commissions that provide independent oversight (i.e. “regulated utilities”), TVA’s past IRP processes have been inaccessible, inequitable, and opaque.

IRPs are complex documents that often have extensive appendices to help readers understand the proposed resource plans based on assumptions and methods used by the utility to develop the plans. The TVA Act, the portion of the federal code that governs TVA, states that TVA must use least-cost planning, but does not provide any guidance on specific assumptions or details of the process that TVA must make public.

State-level IRP regulations often outline specific information or tables that are to be included in each utility’s IRP filing. For instance, the Florida statute governing the Ten Year Site Plans that utilities must file every year ensures that each utility includes at least 16 different “schedules” or tables of information like the historical and forecast load and customer count by customer class.

How has TVA hidden key assumptions in the past? We can look to both its 2019 IRP and the more recent analysis it has performed to propose replacing the Cumberland and Kingston coal plants. Key assumptions in an IRP include the forecasts for electricity demand, generating resource costs, and fuel prices, which are inputs to modeling that drive what resource mix is determined “least cost” by a capacity expansion model.

In the 2019 Draft IRP, TVA presented charts of key assumptions like gas, coal, and carbon price forecasts but not the values behind the charts. In a similar fashion, TVA presented the portfolio additions by resource type in its Draft IRP, but provided that information at a very high level: every 5 years, in gigawatts (1,000 megawatts), and for broad categories like “renewable” instead of breaking out wind and solar. As we described in a blog at the time, we went through various of TVA’s channels to try to get adequate information to inform our comments on the draft IRP through TVA’s National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) process. We were informed that these requests had to go through TVA’s Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) process, despite the tight NEPA comment deadline of 60 calendar days. This resulted in TVA providing some additional documents and information on the Thursday before comments were due on a Monday.

In April of 2022, TVA put out a draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) evaluating the impacts of replacing the Cumberland coal plant with two gas options or a solar and storage option. The modeling behind that EIS is the same type of modeling done in an IRP. Yet the EIS documents barely mentioned the modeling done and did not mention any of the key assumptions or key outcomes. Instead of stating what the total cost would be of all three alternatives considered, TVA presented a chart showing the relative difference between the costs of the two remaining alternatives to its preferred alternative. Even though we explicitly asked for the costs of each alternative through a FOIA request, we were only given the relative numbers between alternatives. So we have no way to know how big the differences between the costs of the alternatives are compared to the overall costs of an alternative. Do they vary by 1% or 98%? Only TVA knows.

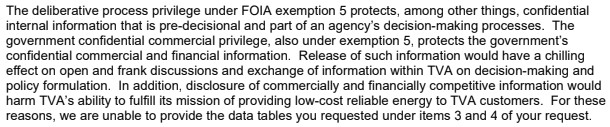

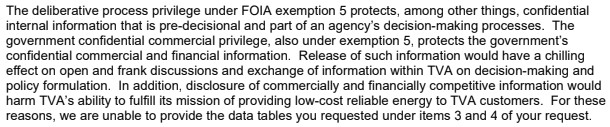

It is also worth noting that TVA uses certain FOIA exemptions rather liberally in order to avoid sharing information. Through our FOIA process related to the Cumberland replacement decision, TVA used the FOIA exemption 5 that protects “internal information that is pre-decisional” in order to refuse to respond to some of our requests. That refusal from TVA was received January 11, 2023. TVA’s Record of Decision in that case appeared in the Federal Register on January 20, 2023. So clearly TVA was not still deciding what to do on January 11. TVA uses this particular FOIA exemption quite often.

Excerpt of TVA’s response to a SACE FOIA request on the Cumberland replacement EIS, received January 11, 2023.

How are these kinds of information requests handled elsewhere? Most states have set rules for discovery requests among parties to a given docket, including IRP dockets. For example, the state of Indiana requires that the utilities respond to these requests within 15 business days. Now, it is true that some states allow utilities to require intervenors to sign some sort of confidentiality agreement before viewing responses to information requests that handle confidential information. That is handled differently in different jurisdictions. But since TVA is not a publicly traded company, and instead is owned by the federal government, it should have a different standard for what it can claim is confidential information.

One way that TVA has claimed legitimacy in the past for its IRP process is through the use of an IRP Working Group as a stakeholder process. In its 2019 IRP, it calls the IRP Working Group “a cornerstone of the public input process for the 2019 IRP.” But contrary to stakeholder processes elsewhere, TVA gets to hand-pick who gets a seat at the table.

For its 2019 IRP, TVA assembled a working group of 20 individuals that TVA claims are representative of various interests across the region. Members of the working group were required to sign a non-disclosure agreement to attend some of the sessions. While materials from these meetings were eventually posted online, meeting agendas were not posted ahead of meetings, meetings themselves were not open to the public or streamed online, and no summaries or minutes from the meetings were made available.

But what if you don’t see anyone in that working group that represents your interests? For example, the 2019 IRP working group included individuals from the city governments of Knoxville and Memphis, but not from other cities and counties big and small across TVA’s territory. If an elected official from Athens, Tennessee wants to be involved in TVA’s IRP, for example, they simply can’t unless they’ve already been invited by TVA leadership to be at the table. With this ability to pick and choose, TVA could exclude anyone that has expressed public opposition to TVA. Specifically, TVA does not include any organizations that have lawsuits against TVA.

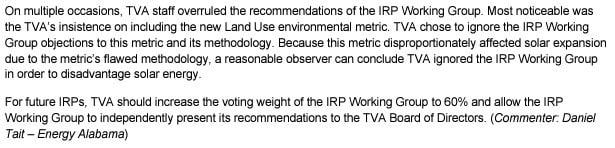

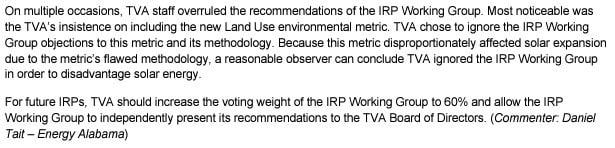

A member of the 2019 IRP working group saw enough flaws in the process to include several comments on it in his comments through the NEPA process on the draft 2019 IRP. Daniel Tait of Energy Alabama, a member of the 2019 IRP working group, called out TVA for overruling decisions made by the IRP working group because TVA itself represented 50% of the voting share of the working group. How is it a stakeholder group if TVA gets half the votes? That’s some strange gerrymandering.

Comment from Daniel Tait of Energy Alabama, member of the 2019 IRP working group, on TVA’s 2019 Draft IRP. Source: Final 2019 IRP EIS, Appendix F

Again, this is not how stakeholder processes are done elsewhere. Duke’s utilities in the Carolinas have been tasked with a stakeholder process to inform its Carbon Plan, and thus IRP, process. While Duke’s stakeholder process has some of its own flaws, stakeholders do not need a special invitation from Duke to participate (though I’m sure Duke wouldn’t mind that setup). Duke hired a facilitator to manage multiple stakeholder meetings on particular topics, registration is open to anyone, meetings are held virtually, and slides, videos, and meeting summaries are all posted online as part of Duke’s IRP portal. And if stakeholders are not happy with the process, they can file comments with the North Carolina Utilities Commission describing the issues with the process and potential solutions.

Most regulated utilities have to present at some sort of hearing in front of their Commission. This is where a utility presents its case by testimony from various witnesses with expertise in a variety of topics. Those witnesses are sworn under oath, make their case, and are asked questions by Commissioners and intervenors. When it is the intervenors’ turn, each intervenor is given the opportunity to make a case with one or more witnesses on relevant topics of their choosing, and again those witnesses are sworn under oath and asked questions by Commissioners and other intervenors, including the utility. Depending on the venue, these hearings can take a few days to a few weeks, are open to the public, and are typically streamed live online.

TVA might present its NEPA process as corollary to a hearing, but let me walk through two real-world examples to show how the same issue would be handled very differently under the two types of processes.

Energy efficiency is a key input to any IRP. TVA’s 2019 IRP was seriously lacking in energy efficiency due to TVA’s assumptions on the cost and availability of energy efficiency, which we pointed out in our comments through the NEPA comment period on the draft IRP. Did this result in any change in the way TVA modeled energy efficiency? Certainly not. TVA pasted our comment in an appendix to its final IRP with a one-paragraph response referring back to the section in the IRP that describes the very modeling assumptions we were disputing.

Energy efficiency has been a key topic in other IRPs, including in South Carolina. When SACE intervened in Dominion South Carolina’s IRP, which was also low on energy efficiency, we included testimony about the cost-effectiveness of energy efficiency as a resource. As a result of the work of SACE and other intervenors, the South Carolina Public Service Commission ordered Dominion to model several energy efficiency scenarios in its next IRP, including up to 2% of annual load. We have seen similar results from Commissions in Georgia and North Carolina.

So while utilities in South Carolina, Georgia, and North Carolina would have liked to be able to pick and choose which comments from intervenors they would like to address in an IRP, it is up to the Commission, and not the utility, if and how those comments and recommendations are integrated. Commissions certainly do not act on all recommendations by intervenors, but they are an independent regulator with expert staff that are able to make key decisions about what changes should or should not be made in a utility’s resource plan. TVA, as we see from the example, has no such independent decision-maker. Instead, it is TVA staff that read all the NEPA comments and decide whether they warrant any change to the IRP (they usually do not) or just a few sentences of response in an appendix.

SACE Executive Director Dr. Stephen A. Smith had the following to say when reflecting on his participation in TVA’s IRP processes through various of its invite-only bodies since its very first IRP working group.

If TVA will not take steps to make its 2024 IRP process more transparent and accessible than previous processes, it is important that the TVA Board of Directors take this opportunity to step up and instruct TVA to make improvements so that the people in the Tennessee Valley have the same opportunities to engage on the future of energy in their region that neighbors served by private utilities currently enjoy.

The post TVA Planning Process Less “Public” than Private Utilities appeared first on SACE | Southern Alliance for Clean Energy.

So the long-term planning process of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), a federally-owned utility that serves 10 million people across seven states in the Southeast, is a big deal. TVA is required to do this planning process, called an Integrated Resource Plan or IRP, at least every five years. Since the last one was finalized in 2019, TVA is due to finish its next plan by the end of next year. Last month, TVA started that ball rolling by opening a comment period for scoping comments through July 3. That “public input” period is essentially perfunctory, as you’ll see as I compare it to public processes done for IRPs elsewhere.

TVA’s IRP Process: Opaque and Inaccessible

Before we embark on another TVA IRP process, it’s helpful to review how these processes have gone in the past, and how likely TVA is to consider your submitted comments in the long-term resource decisions it ultimately makes. Compared to IRP processes for utilities regulated by state Public Service Commissions that provide independent oversight (i.e. “regulated utilities”), TVA’s past IRP processes have been inaccessible, inequitable, and opaque.

TVA has no regulations for what gets published, how to handle information requests

IRPs are complex documents that often have extensive appendices to help readers understand the proposed resource plans based on assumptions and methods used by the utility to develop the plans. The TVA Act, the portion of the federal code that governs TVA, states that TVA must use least-cost planning, but does not provide any guidance on specific assumptions or details of the process that TVA must make public.

State-level IRP regulations often outline specific information or tables that are to be included in each utility’s IRP filing. For instance, the Florida statute governing the Ten Year Site Plans that utilities must file every year ensures that each utility includes at least 16 different “schedules” or tables of information like the historical and forecast load and customer count by customer class.

How has TVA hidden key assumptions in the past? We can look to both its 2019 IRP and the more recent analysis it has performed to propose replacing the Cumberland and Kingston coal plants. Key assumptions in an IRP include the forecasts for electricity demand, generating resource costs, and fuel prices, which are inputs to modeling that drive what resource mix is determined “least cost” by a capacity expansion model.

In the 2019 Draft IRP, TVA presented charts of key assumptions like gas, coal, and carbon price forecasts but not the values behind the charts. In a similar fashion, TVA presented the portfolio additions by resource type in its Draft IRP, but provided that information at a very high level: every 5 years, in gigawatts (1,000 megawatts), and for broad categories like “renewable” instead of breaking out wind and solar. As we described in a blog at the time, we went through various of TVA’s channels to try to get adequate information to inform our comments on the draft IRP through TVA’s National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) process. We were informed that these requests had to go through TVA’s Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) process, despite the tight NEPA comment deadline of 60 calendar days. This resulted in TVA providing some additional documents and information on the Thursday before comments were due on a Monday.

In April of 2022, TVA put out a draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) evaluating the impacts of replacing the Cumberland coal plant with two gas options or a solar and storage option. The modeling behind that EIS is the same type of modeling done in an IRP. Yet the EIS documents barely mentioned the modeling done and did not mention any of the key assumptions or key outcomes. Instead of stating what the total cost would be of all three alternatives considered, TVA presented a chart showing the relative difference between the costs of the two remaining alternatives to its preferred alternative. Even though we explicitly asked for the costs of each alternative through a FOIA request, we were only given the relative numbers between alternatives. So we have no way to know how big the differences between the costs of the alternatives are compared to the overall costs of an alternative. Do they vary by 1% or 98%? Only TVA knows.

It is also worth noting that TVA uses certain FOIA exemptions rather liberally in order to avoid sharing information. Through our FOIA process related to the Cumberland replacement decision, TVA used the FOIA exemption 5 that protects “internal information that is pre-decisional” in order to refuse to respond to some of our requests. That refusal from TVA was received January 11, 2023. TVA’s Record of Decision in that case appeared in the Federal Register on January 20, 2023. So clearly TVA was not still deciding what to do on January 11. TVA uses this particular FOIA exemption quite often.

Excerpt of TVA’s response to a SACE FOIA request on the Cumberland replacement EIS, received January 11, 2023.

How are these kinds of information requests handled elsewhere? Most states have set rules for discovery requests among parties to a given docket, including IRP dockets. For example, the state of Indiana requires that the utilities respond to these requests within 15 business days. Now, it is true that some states allow utilities to require intervenors to sign some sort of confidentiality agreement before viewing responses to information requests that handle confidential information. That is handled differently in different jurisdictions. But since TVA is not a publicly traded company, and instead is owned by the federal government, it should have a different standard for what it can claim is confidential information.

TVA hand-picks its stakeholders

One way that TVA has claimed legitimacy in the past for its IRP process is through the use of an IRP Working Group as a stakeholder process. In its 2019 IRP, it calls the IRP Working Group “a cornerstone of the public input process for the 2019 IRP.” But contrary to stakeholder processes elsewhere, TVA gets to hand-pick who gets a seat at the table.

For its 2019 IRP, TVA assembled a working group of 20 individuals that TVA claims are representative of various interests across the region. Members of the working group were required to sign a non-disclosure agreement to attend some of the sessions. While materials from these meetings were eventually posted online, meeting agendas were not posted ahead of meetings, meetings themselves were not open to the public or streamed online, and no summaries or minutes from the meetings were made available.

But what if you don’t see anyone in that working group that represents your interests? For example, the 2019 IRP working group included individuals from the city governments of Knoxville and Memphis, but not from other cities and counties big and small across TVA’s territory. If an elected official from Athens, Tennessee wants to be involved in TVA’s IRP, for example, they simply can’t unless they’ve already been invited by TVA leadership to be at the table. With this ability to pick and choose, TVA could exclude anyone that has expressed public opposition to TVA. Specifically, TVA does not include any organizations that have lawsuits against TVA.

A member of the 2019 IRP working group saw enough flaws in the process to include several comments on it in his comments through the NEPA process on the draft 2019 IRP. Daniel Tait of Energy Alabama, a member of the 2019 IRP working group, called out TVA for overruling decisions made by the IRP working group because TVA itself represented 50% of the voting share of the working group. How is it a stakeholder group if TVA gets half the votes? That’s some strange gerrymandering.

Comment from Daniel Tait of Energy Alabama, member of the 2019 IRP working group, on TVA’s 2019 Draft IRP. Source: Final 2019 IRP EIS, Appendix F

TVA lacks oversight and input built into other regional utilities’ IRP

Again, this is not how stakeholder processes are done elsewhere. Duke’s utilities in the Carolinas have been tasked with a stakeholder process to inform its Carbon Plan, and thus IRP, process. While Duke’s stakeholder process has some of its own flaws, stakeholders do not need a special invitation from Duke to participate (though I’m sure Duke wouldn’t mind that setup). Duke hired a facilitator to manage multiple stakeholder meetings on particular topics, registration is open to anyone, meetings are held virtually, and slides, videos, and meeting summaries are all posted online as part of Duke’s IRP portal. And if stakeholders are not happy with the process, they can file comments with the North Carolina Utilities Commission describing the issues with the process and potential solutions.

TVA lacks a hearing overseen by independent entity, TVA itself picks how to respond to feedback

Most regulated utilities have to present at some sort of hearing in front of their Commission. This is where a utility presents its case by testimony from various witnesses with expertise in a variety of topics. Those witnesses are sworn under oath, make their case, and are asked questions by Commissioners and intervenors. When it is the intervenors’ turn, each intervenor is given the opportunity to make a case with one or more witnesses on relevant topics of their choosing, and again those witnesses are sworn under oath and asked questions by Commissioners and other intervenors, including the utility. Depending on the venue, these hearings can take a few days to a few weeks, are open to the public, and are typically streamed live online.

TVA might present its NEPA process as corollary to a hearing, but let me walk through two real-world examples to show how the same issue would be handled very differently under the two types of processes.

Energy efficiency is a key input to any IRP. TVA’s 2019 IRP was seriously lacking in energy efficiency due to TVA’s assumptions on the cost and availability of energy efficiency, which we pointed out in our comments through the NEPA comment period on the draft IRP. Did this result in any change in the way TVA modeled energy efficiency? Certainly not. TVA pasted our comment in an appendix to its final IRP with a one-paragraph response referring back to the section in the IRP that describes the very modeling assumptions we were disputing.

Energy efficiency has been a key topic in other IRPs, including in South Carolina. When SACE intervened in Dominion South Carolina’s IRP, which was also low on energy efficiency, we included testimony about the cost-effectiveness of energy efficiency as a resource. As a result of the work of SACE and other intervenors, the South Carolina Public Service Commission ordered Dominion to model several energy efficiency scenarios in its next IRP, including up to 2% of annual load. We have seen similar results from Commissions in Georgia and North Carolina.

So while utilities in South Carolina, Georgia, and North Carolina would have liked to be able to pick and choose which comments from intervenors they would like to address in an IRP, it is up to the Commission, and not the utility, if and how those comments and recommendations are integrated. Commissions certainly do not act on all recommendations by intervenors, but they are an independent regulator with expert staff that are able to make key decisions about what changes should or should not be made in a utility’s resource plan. TVA, as we see from the example, has no such independent decision-maker. Instead, it is TVA staff that read all the NEPA comments and decide whether they warrant any change to the IRP (they usually do not) or just a few sentences of response in an appendix.

A reflection from a longtime participant in TVA’s IRP processes

SACE Executive Director Dr. Stephen A. Smith had the following to say when reflecting on his participation in TVA’s IRP processes through various of its invite-only bodies since its very first IRP working group.

“My experience with TVA’s IRP public participation process is that if you are not selected by TVA leadership to be part of the ‘IRP Working Group’ you are at an extreme disadvantage in accessing critical information in a timely fashion. Without timely access to the information, there is no opportunity for meaningful input into the important assumptions TVA staff will use for input into the models that produce their short- and long-term plans. It is a classic example of a ‘garbage in garbage out’ scenario. If the assumptions are not robust and accurate, the quality of the plan goes down with the risk and cost for customers going up. TVA leadership should not selectively ‘hide the ball’ on critical public information.” ~Dr. Stephen A. Smith, SACE Executive Director

The Time is Now for TVA to Improve its IRP Process

If TVA will not take steps to make its 2024 IRP process more transparent and accessible than previous processes, it is important that the TVA Board of Directors take this opportunity to step up and instruct TVA to make improvements so that the people in the Tennessee Valley have the same opportunities to engage on the future of energy in their region that neighbors served by private utilities currently enjoy.

The post TVA Planning Process Less “Public” than Private Utilities appeared first on SACE | Southern Alliance for Clean Energy.